Ringmore History

Ringmore is a beautiful, secluded village in the heart of the South Hams. Lying just back from the coast, it spreads part way down a quiet green valley that looks westward to Ayrmer Cove and the English Channel.

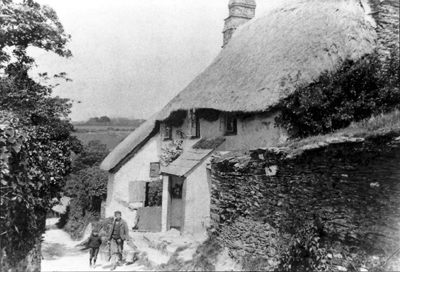

The parish of Ringmore extends to 1,128 acres and includes at its southern boundary the shoreline hamlet of Challaborough and, to the north, a group of houses at Marwell. Its coastal land as well as an extensive acreage of hinterland are owned by the National Trust, and a large part of the village is designated as a Conservation Area. The approaches to the village are narrow, winding and steep, and its leafy inner paths impart a sense of undisturbed peace and antiquity to the unhurried walker. By common consent there is no street lighting and, as yet, no mobile `phone mast in this tranquil place.

The Domesday Book contains mention of Ringmore, calling it `Reimore’, and there was once a manor (an estate) of Ringmore that changed hands through the centuries  and which was not parcelled up and sold until 1908. But it seems there never was a resident lord of the manor, and so no large manorial house to provide employment and keep written records that might reveal to us the story of Ringmore’s more distant past.

and which was not parcelled up and sold until 1908. But it seems there never was a resident lord of the manor, and so no large manorial house to provide employment and keep written records that might reveal to us the story of Ringmore’s more distant past.

What is certainly known is that the small sandy bay at Challaborough was once Ringmore’s `port’. From there the fishing boats were launched to bring home the gleaming silver shoals of pilchards, and to rescue seafarers wrecked  on perilous rocks at nearby Burgh Island. There, too, at Challaborough, in more recent times, coal was unloaded from cargo vessels and then carted up for sale and distribution around the parish. The old Coastguard cottages still stand ruggedly at Challaborough’s shoreline.

on perilous rocks at nearby Burgh Island. There, too, at Challaborough, in more recent times, coal was unloaded from cargo vessels and then carted up for sale and distribution around the parish. The old Coastguard cottages still stand ruggedly at Challaborough’s shoreline.

Thrilling and desperate times came to Ringmore during the Civil Wars of the seventeenth century when the All Hallows’ parish priest, William Lane, declared himself to be loyal to the King and against Cromwell. In retaliation, a contingent of Cromwell’s men came from Plymouth by sea, landed at Ayrmer and plunged up the valley, burning down the Rectory and taking prisoner two of William Lane’s sons. Lane took refuge in a secret room in the tower of All Hallows and was carefully looked after by devoted parishioners for many weeks before managing to escape to France. Sadly, when he eventually returned and was walking home from London to Devon after petitioning to be reinstated, he drank bad water at the roadside and died of a fever, forty miles short of home. He is buried under the communion table in the church at Alphington, just outside Exeter.

Ringmore’s thirteenth-century church, All Hallows, stands at a confluence of lanes at the head of the village. There is evidence in its stonework to show that one part of it - what is now the north transept - is Saxon in origin. Much of the building as it now stands was added to that Saxon chapel in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

In 1860, when both church and village were struggling to overcome poverty and decay, a remarkable new rector, Francis Charles Hingeston-Randolph, arrived at All Hallows. In the first three years of his incumbency he restored the church, built a village school, and revitalised the lives of his parishioners. His sensitive restoration of the church uncovered a unique wall-painting on the chancel arch, and repaired its crumbling masonry and broken bells as well as its roof and shattered windows. He bought and installed a new Bevington organ, and provided the whole building with richly colourful decorations and furnishings. The church now has a Grade 2 (starred) listing.

The twentieth century brought many changes to Ringmore. Its people, once a predominantly self-reliant farming and fishing community, gradually left the land and the sea. Many of the ancient cottages were bought by incomers seeking a peaceful retirement, a garden to till, or somewhere to sail a small boat. A few of the old dwellings became seasonal holiday homes, and the population has steadied out at between 200 and 240.

What has not changed except, perhaps, to gain in strength, is the awareness of Ringmore as a place of great natural charm and loveliness. Those who live there think of it as having a rare and special character.